I was born in Singapore to a really large, multi-racial family. Mum is a half-Gujarati and half-Swiss which is a very unusual combo. Dad is of Malayalee origins, which is from the Kerala region, south of India, but was born in Singapore. Due to the difference in their backgrounds, neither side agreed who was paying for the wedding, so they paid for it themselves, having a temple wedding but not a reception. My husband Chris – who is of Caucasian descent – and I married in Melbourne, but we also had the cultural temple wedding in Singapore.

It was the same temple where Mum and Dad had their wedding and we gave our first dance to them. It was really nice, watching them waltzing to Engelbert Humperdinck. They were crying as they never had that big reception, but received it 30 years later.

That’s the migrant story. We do everything we can so our kids can have a different experience growing up.

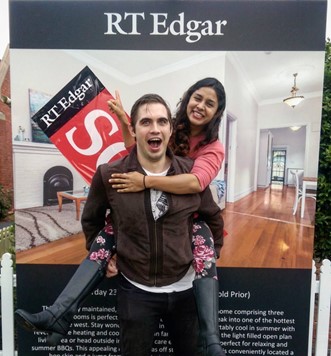

In the early days of Chris and I getting to know each other, I didn’t think he was interested in me and it hurt. In a flash of impulsivity, I applied for an exchange program to the United States in an attempt to get far, far away. Turns out, he was just really, really shy. Whoops! We started dating in March, and I received the acceptance letter in April.

We were only 21, and Chris promised he’d wait for me to come back.

While I was in the United States, Mum said she’s going to Melbourne, and would love to meet my brother, who then used to live in Melbourne. She also suggested she’d like to meet Chris. Even though it sounded crazy, Chris introduced my mum to his mum, and they had the time of their lives. Chris would drive them around, and the two women were having a blast with wine tasting. I remember thinking, “This is so weird, but I love that they’re getting along.”

When we first started dating, he said his favourite food is laksa. I told him the laksa in Melbourne is not the proper kind that does all the right things. So I brought him to Singapore, and introduced him to Katong Laksa. Ahh, real laksa.

Growing up in Singapore, we lived on the East Coast of the island, with our house being two minutes from the beach. I liked being by myself. I used to sit at the breakwater and stare at the ocean, and spent a lot of time by the water.

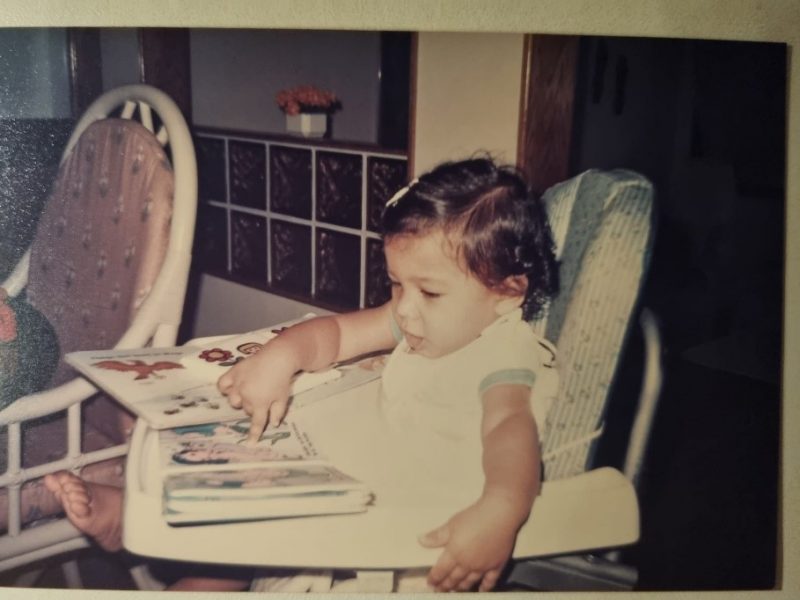

When I was younger, I always thought I had a superpower, and wonder why can’t people hear what I hear, or feel what I feel. Unfortunately, growing up in an Asian culture means we don’t talk much about our feelings easily. I used to go to the library to read more about people, as I didn’t understand them. I’ve clearly always enjoyed reading and the made up world of fantasy more than people-ing.

I had a lot of friends, and was surrounded by a lot people, but I never really had a best friend. I had groups, but was always on the outer edge of friendship. I would get asked to go out all the time, but I didn’t have the energy for keeping up with the gossip around other people and dealing with the crowds.

At the age of 26, I began to recognise the term ADHD, and understood the symptoms. However I wasn’t formally diagnosed until the age of 31, and then later receiving a diagnosis of autism too.

When I received my primary school grading results, I didn’t do really well. At that time, news stories of children jumping to their death when they didn’t do well was prevalent. I didn’t know how to proceed so I went to the MacDonalds across the road to call my parents to see if I was allowed to come home. I was. Whew!

In hindsight, I now realised my ADHD didn’t allow me to process new languages well, so I couldn’t grasp a second language (Bahasa Melayu), which brought my grades down. What I would have given to know the deep why.

I only qualified for a local government high school, and it was the *worst*experience of my life.

It was where the neighbourhood kids go to, many of who were in gangs. The disciplinary master had a gun in the holster, and I was terrified. My parents did everything in their power to appeal to different schools to get me out of there. In order to qualify into a ‘better’ school, I had to agree to join the Track and Field team, even though I was a swimmer.

I was juggling swimming and athletics, and had to keep my grades up as part of the agreement. I came in with the lowest entry score in the school, and continued to fail through school, landing me in the bottom 30 of the cohort.

I am so very grateful for my school for having invited Adam Khoo, a famous motivational speaker, to speak to us in the bottom 30. His iconic tagline is “I am gifted, so are you!”, which is kind of hilarious when you’re in the bottom 30. But I now realise that there are ADHD-friendly ways of learning and absorbing information. He taught me how to mindmap, to use colour and music to engage with my studies, and that gave me the platform to go forward.

I arrived in Melbourne in 2007 as my brother was here. I was looking to explore Australia as a fit for my strong, intense emotionality, which was always out of sync with Singaporean conservative culture. I went to Melbourne Uni, pursuing an Arts degree majoring in Criminology and Psychology, and pursued my Masters at Monash. My first job as a Psychologist was in Melton, so we picked a spot in the Inner West to balance Chris’ city job and my outer west role, picking Newport to build our family.

I worked for another private practice to start with. However, my first-born son was born with laryngomalacia and neutropenia, meaning he has a floppy larynx and low white blood cells. A simple cold or virus could kill him. Every time he got a cold, we had to go to the hospital, or at least be on standby. In our first 2 years we had been to the hospital 6 times. It was a tough start to parenthood, but my employer found it hard to meet my needs for flexibility. I was that parent running into the childcare centre right before it closed.

I wanted flexibility and financial freedom, a career rather than a job, and one that helped me be there for all those hospital trips. I began renting a room around the corner from here up in Charles Street, at the Osteopathy clinic. It was liberating, knowing I could dictate my own time.

My business grew out of that room, and I had to increase my hours to meet the demand. I worked 5 days a week at my other job, and at my own practice on Saturdays, just to build my practice up. In 2021, it became my sole source of income. I was coming out of maternity leave with my second child, and I made the decision to make start my business full time.

If I could choose where this practice was going to go?

I would love to set up a parenting community to help them navigate support for their child. It isn’t all doom and gloom. Community care is a great thing. It’s a way for people leaning on each other to feel supported in their lives. For neurodivergent families, it’s easy to feel isolated. If we build the community, they’d think ‘Hang on, I have that village. When I’m low they help me and they they’re low I help them.’ This is society’s antidote to isolation – community.

I do parenting courses these days to make the information in my head accessible. So many parents juggle work and attending to kids’ needs that online material at their own time and pace just works. However, I’d love to write more resources to fill any gaps. Books are such an affordable way to access the same information. You’ll get the same out of a $220 psychology session and a $27 book, and with a book, you get something visual.

Reflecting back….

I realise now that the unique experiences in my life happened when I didn’t understand my brain and tried to slug it through a neurotypical lens. I didn’t even realise I could possibly be gifted, because ADHD had me failing so badly at school. Now? I know my brain so much more. I have a business that is thriving BECAUSE of the way my brain works.

Thanks to this leaning in, it’s helping people all around Australia. I just wrote the first children’s book of its kind to explain what it’s like to be both autistic and ADHD, called The Rainbow Brain. If there’s a problem, my brain fires into solution mode without overthinking why I shouldn’t do it.

When I wrote The Brain Forest, people around the world started talking to me. I struggled with that.

It’s a very Singaporean thing, but also autistic. While in Australia, the culture focuses on you, in Singapore this would not fly. We have to give honour to our society and family first. I like to think of myself as the spokesperson for the community. It comes back to the collectivist culture. I feel uncomfortable if someone says ‘You’re doing a good job’. I’m like ‘No, this is a collection of everything I’ve learnt from my clients. It’s from being in this community that’s helped me write about these experiences.’

Back to our roots…

We straddle life between Melbourne and Singapore, and visit Singapore once a year. We don’t do the touristy things, but still do the local stuff like chilli crabs and drink tea from a plastic bag. (Sorry, environment!). The most important thing is spending time with my grandparents, while Chris and the kids get to live Singapore-style. Around my house there are still chickens crossing the road. It’s literally a little pocket where there are still roosters in the kampung (‘village’ in Bahasa Melayu.) and wild boars around.

One fun fact about me?

I missed out on the Olympic training time trials for the Singapore swim team by 0.02 seconds. I thought that was the moment I walked away from swimming, as I’m not chasing a 0.02 seconds goal. It was a relentless 15 hour a week training routine, and I couldn’t do it anymore.

Athletics was my identity back then, and now I have a different identity as author, parent, psychologist and speaker. And hopefully? The fun parent. (Fight to the death, Chris!)